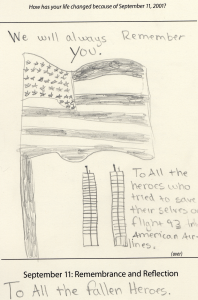

A visitor sketched this while reflecting on the events of September 11.

Visitors to Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History’s exhibit September 11: Bearing Witness to History on the tenth anniversary of September 11 were given a unique object-oriented experience. The exhibit featured items the museum has chosen to preserve in perpetuity laid out on tables, with short labels, and no glass cases. Visitors were encouraged to reflect upon personal memories and to consider the the ways in which September 11 has changed their lives. Visitors were invited to become part of the collection by telling their stories. Comment cards included questions regarding demographic information, such as age, place of residence, and gender, and where they heard about the exhibit. Visitors were invited to respond to one of the following prompts:

- “How did you witness history on September 11, 2011? Tell us your story. Feel free to write or sketch.”

- “How was your life changed because of September 11, 2001?”

Visitor responses to those questions are preserved in the September 11 Digital Archive’s collection Smithsonian National Museum of American History, Visitor Responses on the Tenth Anniversary in 2011. Exhibit visitors came not only from the United States but also countries across the globe, including South Africa, and ranged widely in age, such as this respondent, who was only three months old when the attacks occurred. Some visitors to the exhibit chose to sketch, such as one individual who drew a cell phone with no service, or this nine-year-old, who drew the two towers.

Many visitors reflected on their sensory experiences of September 11. This visitor landed at Newark Airport at 8:45 in the morning and “noticed smoke coming out of the WTC.” By the time she left the airport, the second plane had hit, and she pulled over in her car and “watched, horrified. Life has never again been quite the same.” Another respondent saw the second tower burning and its collapse, which she described as the building coming “apart like someone had unzipped it down the middle.” While not witnessing the event in person, this individual watched television coverage and “tried to rationalize it away as a wierd [sic] movie or ‘what if documentary.’ Then it hit me that what I was watching was actually happening.” Other respondents remembered the smell. One visitor left his beret in his office at the Pentagon after evacuating, and said that he “can still smell smoke and jet fuel on the beret.” Another individual noted that he continues to be haunted by the unique, terrible, and acrid smell. Other visitors reflected upon the absence of sound in the hours and days following the attacks. A native to Washington, DC, one respondent found the silence that followed a “stunning change” because she was so used to hearing the sounds of planes flying overhead, and found the silence comforting because it meant no more planes could attack American targets. This visitor also remembered the quiet in the days after the attacks, writing that “everything was still.”

Some respondents reflected on their work, volunteer efforts, and the ways in which they serve others. One visitor wrote that her husband, a servicemember in the Army, has been sent to Iraq twice, while another was “honored to work at TSA.” Justin said that he “didn’t have much of a sense of patriotism” prior to September 11, but after the attacks he he was motivated to “help my country and to prevent future occurences [sic] such as this…I enlisted in the Navy.” Melissa Cummings’ father boarded a flight the morning of September 11, shortly before Flight 77 which crashed into the Pentagon. She now volunteers at her local fire and rescue service. Visitors to the exhibit included first responders, such as Chaplain Glenn George, who worked for two weeks at Ground Zero, and this individual, who was in an Army mortuary affairs unit and worked 12 to 14 hour shifts at night during the recovery operations at the Pentagon. One respondent’s brother, Ray, was part of FDNY Engine 28 and barely made it out of the North Tower. Ray died ten years later after being diagnosed with multiple myeloma, which his sister believes is related to his work at Ground Zero.

Exhibit visitors discussed the ways in which September 11 affected them emotionally. Megan Hornbeek wrote that every time she flies she wonders “if I would have the courage to take my plane down to prevent additional losses.” This visitor said that her daughter felt safer after Osama Bin Laden was killed. Other visitors expressed feelings of hope, with Edward Lopez writing, “The phoenix will rise from the ashes. Always will.” Other visitors were more cautious, including this individual, who said that “we still must learn to forgive. Not forget, but forgive. I still haven’t fully forgiven yet.” Some individuals mentioned an overwhelming feeling of unity with other Americans and even the world. One visitor felt that after September 11 “the whole country became an American. Even citizens of other countries became American.” Visitors also documented their feelings of patriotism, including this respondent, who “became and remain[s] fiercely patriotic.” Many visitors reflected and remembered friends and family who died on September 11, such as this individual whose friends died in the Pentagon, and this respondent whose friends died on American Airlines Flight 77.

Visitors to the exhibit reflected on the ways in which they were personally affected by Islamophobic sentiment following September 11. One individual wrote “a classmate…said, ‘Your people are responsible for this.’ Since that day, being Afghan American has taken on new meaning and new importance in my life.” Another visitor said the events of September 11 “made it more difficult for my husband and I to become lawful residents [of the United States]” and began to doubt whether they wanted to remain in the country. They chose to stay. Her husband joined the Army and she volunteers for the Army Community Services.

Other visitors cautioned against being fearful and intolerant. One individual urged people to “not misdirect anger…to a religious group but to the criminals.” “I will not raise my girls to be a part of the hate in the world,” wrote another. Therese Quinn organized interfaith memorials a week after the attacks after witnessing Muslim women in her community being harassed and threatened. This respondent, who was in college at the time of the attacks, saw Middle Eastern women who lived on her dormitory floor harassed following September 11, and sends “love to all who are still afraid.” Another visitor now tries harder to “see the good/best in people” after feeling appalled at the treatment of Middle Easterners following September 11. Captain Steve Bowen of the Marine Corps wrote: “Let us honor our dead, bind up our wounds and perhaps look to solve our problems through frank discussion and open minds.”

This collection of over 1,300 items is nested under Smithsonian National Museum of American History Collections and would be of interest to people studying memory, historical trauma, patriotic sentiment, Islamophobia in America, and post-September 11 America more generally.